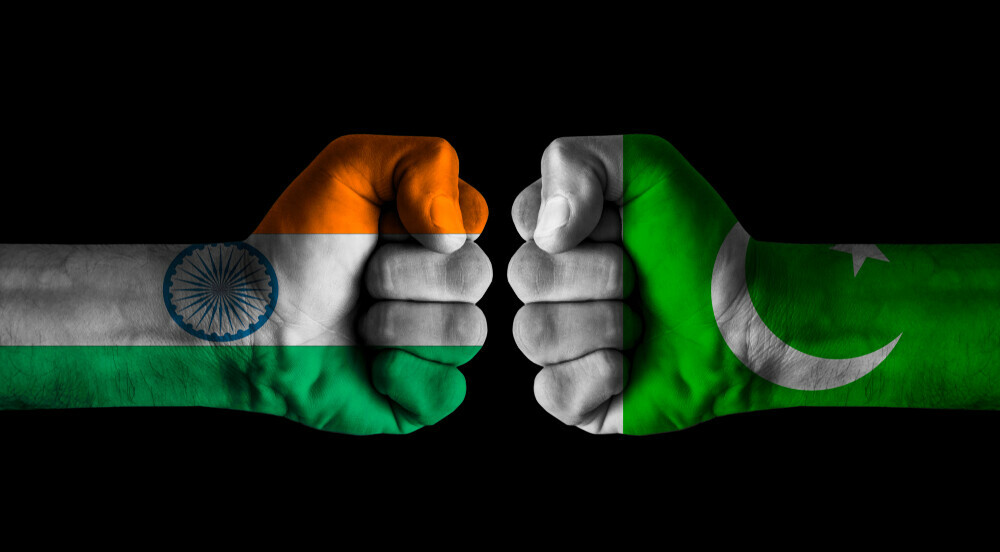

One of the most significant concerns facing the administration that is elected in India’s forthcoming general election, which takes place from April 19 to June 1, is how to handle the strained ties between the nation and its problematic neighbour, Pakistan. It could be easy to say: not much.

Up until recently, there was some optimism that the first half of 2024 would bring elections in both countries, possibly offering a chance for a new beginning. However, after Pakistan’s contentious election in February, all hope for the future of the two countries quickly vanished. The new government’s legitimacy is being questioned by many, with the popular former prime minister Imran Khan and his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party being disqualified from running.

A weak Pakistani coalition government propped up by the military is unlikely to be able to undertake any bold diplomatic initiative toward India, especially because Khan’s supporters, who consider themselves unfairly deprived of power, are liable to challenge any significant policy change. Under these circumstances, India will probably be inclined to maintain its policy of watchful “benign neglect” toward Pakistan.

As it stands, India and Pakistan maintain diplomatic relations at the charge d’affaires level (a notch below the ambassadorial level) but engage on a few issues and speak past each other in the few forums in which they both participate. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been left moribund by their mutual hostility, having gone years without a meeting.

Moreover, bilateral trade is minimal, and exchanges among ordinary people are limited. Indian citizens struggle to get visas to visit Pakistan, and vice versa. Even in sporting events, the two countries rarely compete with each other outside of international tournaments. In short, India and Pakistan are next-door neighbours who are not on speaking terms—and, in India’s view, that is just fine.

India could not always afford to ignore Pakistan, which was long a source of terrorism directed at India. Most notorious, in November 2008, a terrorist organisation from Pakistan, the Lashkar-e-Taiba, carried out a four-day shooting and bombing campaign in Mumbai, killing over 170 people.

The bilateral relationship never recovered. There have been numerous moments when a thaw seemed likely—for example, during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s unplanned stopover in Lahore for then-Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s birthday celebration in 2015. But progress has always been disrupted by another Pakistani-directed terror attack.

As long as Pakistan was unable or unwilling to curb Islamist terrorism from within its borders, India concluded, better bilateral relations would remain elusive. So, in 2019, when Pakistan withdrew its high commissioner from Delhi in protest of Indian policy in Kashmir, India did not resist; on the contrary, it preferred things that way.

Today, India has even less reason to engage with Pakistan. With internal security challenges—especially in its western borderlands of Baluchistan (near Iran) and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (near Afghanistan)—-claiming its attention, Pakistan has little capacity to launch any serious attack on its neighbour. Instead, Pakistan’s military establishment, led by General Asim Munir, has been using those internal security challenges—including those that have arisen directly from groups Pakistan fostered as weapons against India—as a pretext to consolidate its control over the Pakistani state.

It was Munir’s predecessor, General Qamar Jawed Bajwa, who in 2018 engineered the “managed election” of Imran Khan as prime minister. The military was seeking an alternative to the two main political parties—the Pakistan People’s Party and the Pakistan Muslim League—which had alternated in power since the 1970s. (Both had been repeatedly ousted by the military leaders pulling strings behind the scenes.)

But Bajwa backed the wrong horse. Once in power, Khan—a charismatic former cricket star with a playboy image who had transformed himself into a radical Islamist married to a Muslim religious figure—was unwilling to play by the military’s rules. Articulating a fiercely nationalist and Islamist message, and questioning the military’s authority, Khan increasingly asserted his independence—and developed a strong national following.

By April 2022, the military had had enough and arranged Khan’s dismissal. This was not an entirely unpopular action abroad, as Khan had alienated virtually all of Pakistan’s traditional allies. He had celebrated the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan, publicly accused the United States of plotting to overthrow him, and met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow hours after Putin launched Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Khan had also antagonised China by disparaging its China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project. And, by aligning Pakistan with Turkey and Malaysia on some issues, he was seen as undermining Saudi Arabia’s leadership of the Islamic world.

Read more here.